When it comes to heavy vehicles, one of the most dangerous assumptions is that “the load is heavy, so it won’t move.” In reality, a truck’s cargo is subjected to powerful forces every time the vehicle brakes, turns, or accelerates. Without proper restraint, these forces can shift, topple, or even eject the load, endangering the driver and everyone else on the road.

Understanding the physics of load movement is the key to building safe, compliant transport operations. We’ll be using key information drawn from the 2025 Load Restraint Guide to explain these principals.

Why Weight Alone Doesn’t Hold a Load in Place

The heavier a load, the greater the forces it generates. A 10-tonne load can exert 8 tonnes of forward force during sudden braking. That’s enough to break through headboards, push into cabins, or overturn vehicles if not restrained properly.

Simply relying on gravity is never enough, especially when normal driving conditions include braking, cornering, changes in slope, rough road surfaces, and wind resistance. (Load Restraint Guide 2025, pp. 7–9)

The Key Forces Acting on Loads

The Loading Performance Standards set out the minimum restraint strength required to keep loads secure under real driving conditions. A load restraint system must be able to withstand:

- Forward force (braking): up to 0.8g (80% of the load’s weight)

- Rearward force (acceleration or reversing): up to 0.5g (50% of weight)

- Sideways force (cornering): up to 0.5g (50% of weight)

- Vertical force (bumpy roads): up to 0.2g (20% of weight, if relying on friction)

(pp. 4–5, 8)

In practice, this means restraint systems must be strong enough to keep a load in place not only during routine transport, but also in emergency situations like heavy braking or sudden swerves.

Real-World Scenarios

- Emergency braking: A pallet stack shifts forward, slamming into the cabin wall.

- Cornering with “live” loads: Livestock or tankers of liquid move inside their container, destabilising the vehicle and increasing rollover risk.

- Uneven roads: Lashings loosen as loads bounce, reducing restraint effectiveness.

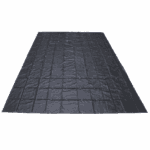

- Slippery surfaces: Steel pipes on smooth steel decks slide easily unless friction is increased with timber or anti-slip mats.

The Role of Friction

Friction is what makes tie-down methods effective. The clamping force from straps or chains presses the load onto the vehicle deck, creating resistance against movement.

But not all surfaces provide equal friction:

- Wet or greasy steel on steel → very low friction

- Smooth steel on timber → medium friction

- Rusty steel on timber → high friction

- Smooth steel on rubber mats → high friction

(pp. 23–25)

Using timber dunnage or rubber load mats can drastically reduce the number of lashings needed to meet the Performance Standards.

Why This Matters for Business

Failing to restrain a load properly doesn’t just risk lives, it can damage your company’s reputation, cost you contracts, and lead to higher insurance premiums. Meeting the Performance Standards isn’t just about compliance, it’s about protecting your people, your freight, and your bottom line.

Final Thoughts

Load restraint is applied physics in action. Every time a vehicle brakes, turns, or accelerates, cargo is put under extreme stress. By understanding the forces at play, and designing restraint systems to withstand them, operators can prevent incidents, protect drivers, and build a stronger culture of safety and compliance.

You May Also Be Interested In

How to Manage Your Fatigue: A Fatigue Management Guide for Heavy Vehicle Operators

Changes in New ADG Code Edition 7.9 Compared to Edition 7.8

Why Load Distribution and Axle Weight Compliance Matter in Heavy Vehicle Transport

What does Line Haul mean in Trucking?